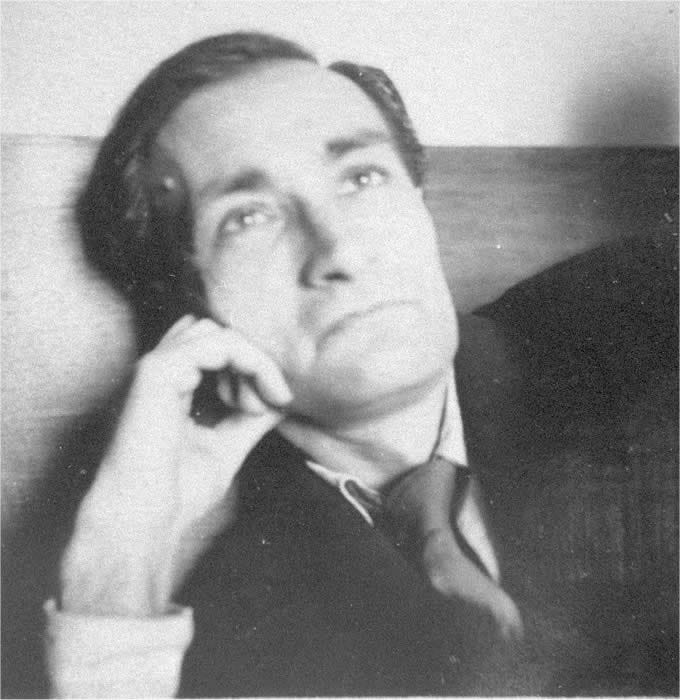

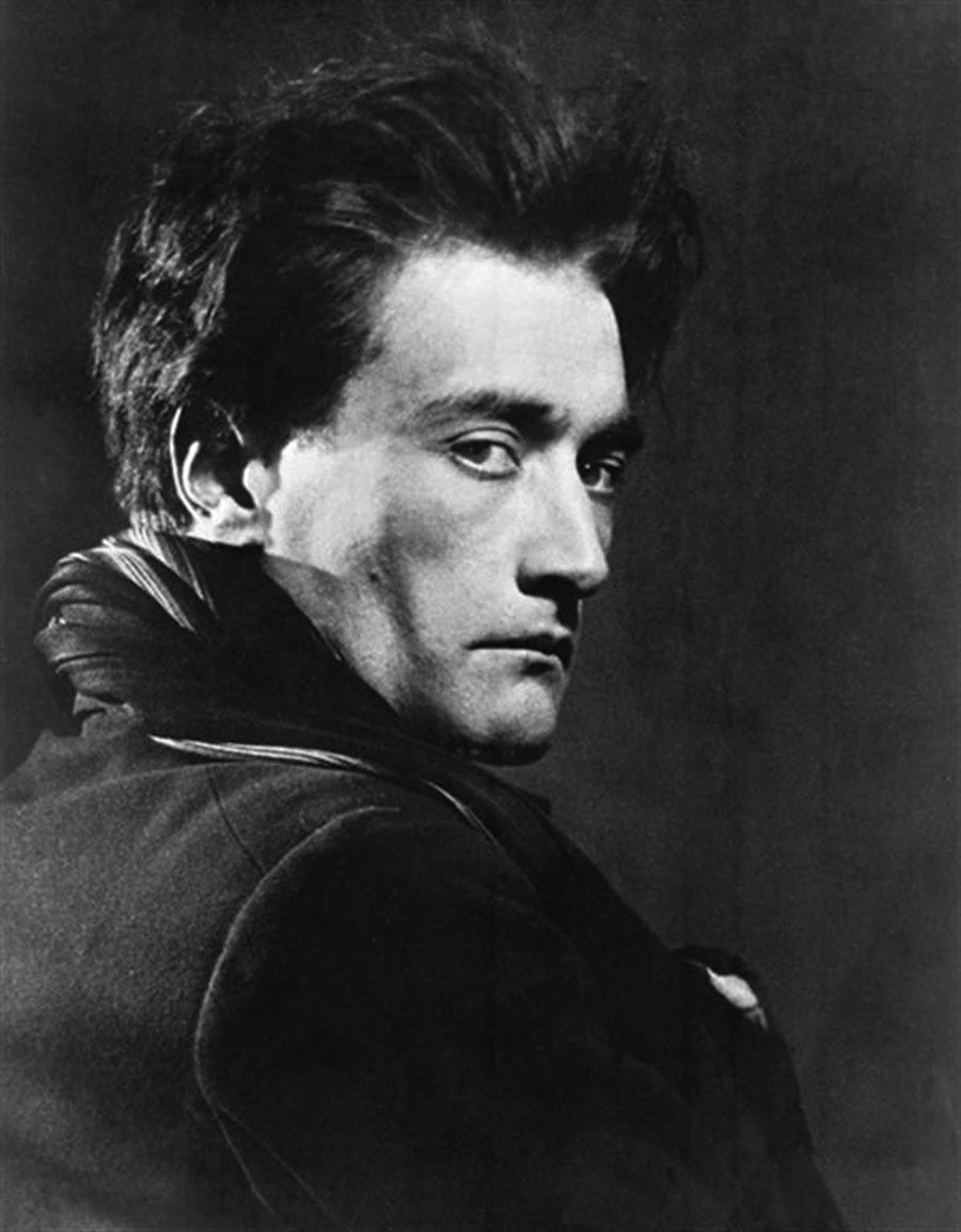

Is there a more magnificent face than the face of Antonin Artaud? For my entire life, I have always been in the presence of his face. My father, along with portraits of Brigitte Bardot and Jean Cocteau, would have an image of Artaud by his work table in Beverly Glen, and later in his studio both in the Glen and Topanga. I was a teenager when I saw Carl Theodor Dreyer’s “The Passion of Joan of Arc,” and like others, I was very much impressed with the face of Renée Jeanne Falconetti as Joan. Like Artaud, Falconetti suffered from mental illness all throughout her life, and eventually committed suicide in Brazil in 1946. When I was working at Beyond Baroque, Viggo Mortensen took me to see “The Passion of Joan of Arc, ” which at the time, he was totally obsessed with the film. He brought me along because he just liked to share his love for the film and who he considered the greatest actress. Falconetti! He also knew I was a colossal Artaud fan, and the scenes in the movie, to me, are dueling faces at work, which is quite remarkable, because Artaud looks so calm, almost evil in a tranquil sense.

When I found myself in Tokyo, I was fortunate to see Kabuki theater in the Ginza, and what I found utterly fascinating was how the audience re-interacts with the actors and what was happening on the stage. There were moments when it seems that the audience becomes part of the theater play. When one walks into the theater, the lighting on the audience side is not darkened. So one cannot only see what is occurring on the stage in front of you, but one is also aware of what the audience is doing. For instance, I was surprised to hear people talk in normal tones during the performance. After a while, once my ears and eyes become accustomed to the “new’ environment, I accepted that the whole theater or building was a performance. One also notices how flat the Kabuki play looks on the stage. No one is highlighted, and it is like seeing a film of a John Ford landscape in Utah, where mountain peaks match the importance of the human figures traveling in that landscape.

When Artaud saw Balinese dancers perform at the Paris Colonial Expo, he must have been affected by the technique and aesthetic of accepting the audience as part of the performance. Also most important is the ritual aspect of the performance and how the dancers use all parts of their body to express themselves, including head and eyes movements. Kabuki is over-the-top as well, and one follows the narrative by its grand gestures than say the quiet moments.

Artaud wrote a play called “Jet of Blood” which starts off with a young man and a young girl repeating the lines, “I love you, and everything is beautiful, ” “You love me, and everything is beautiful.” They repeat the lines in different accents and styles to each other, then when the man comments that “the world is beautifully built and well ordered” - a sudden violent storm appears, including a hurricane which separates the man and girl, with two stars colliding, and assorted objects falling from the sky. Mayhem rules in the world of Artaud.

Artaud is an artist whose life is not separated from his art. An ill man all through his life, plus an addiction to hard narcotics made him vulnerable to the outside world. His mania got worse when he obtained a walking stick of knotted wood and was convinced that this cane once belongs to St. Patrick as well as Lucifer and Jesus Christ. He spent the last years in a mental hospital, and even though he didn’t do many performances either on film or on the stage, his writings have become influential literature for poets, actors, and those who are abused by the system of living in a world of not their making. I, myself, can not escape his influence, especially with respect how he sees space, distance, and the performance that somehow falls between the different categories. To provoke an audience is one way of changing the world. To feel, to create, and throw oneself in the storm that is society is genuinely wonderful. Unless that society is there to reject and harm you.