Jumping Back Into The Surrealists

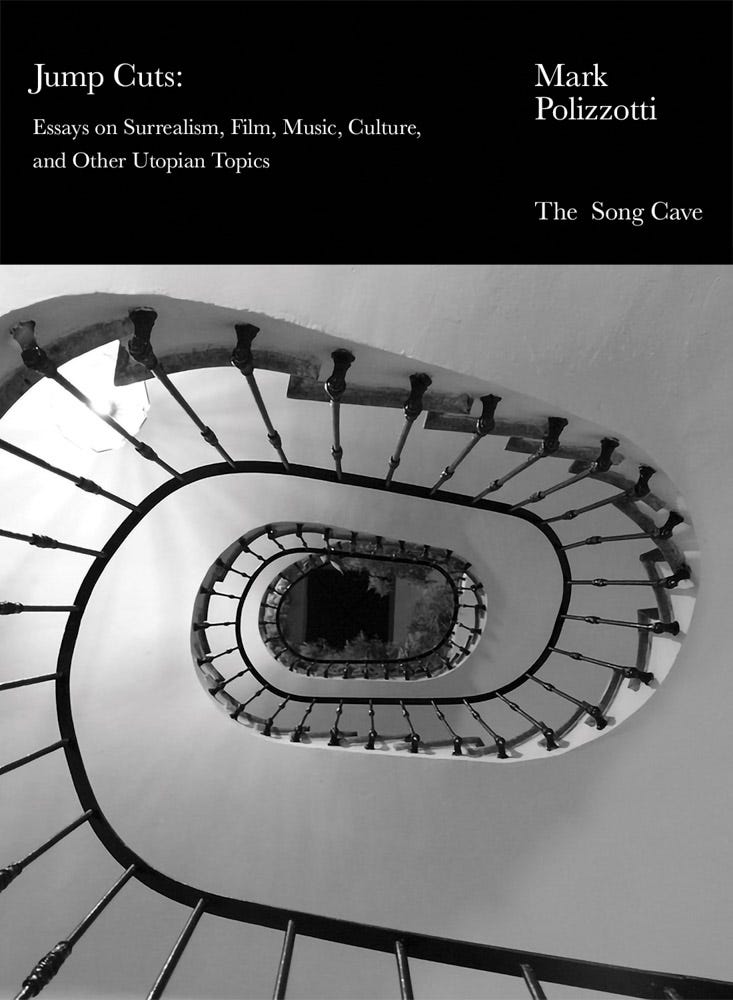

"Jump Cuts "by Mark Polizzotti (The Song Cave, 2025) ISBN: 9798991298834

There is something in the air, as if the presence of André Breton and the Surrealists is returning. I can still feel their significance, even though I haven’t consciously thought of them in years. My subconscious, however, discovered them long ago—when I was a teenager, through my father, Wallace Berman. I grew up in a home where Surrealist texts and books were part of the décor, and where group photographs of the Surrealists often appeared. It seemed you had to be exceptionally handsome to belong to Surrealism.

Reading the great translator and writer Mark Polizzotti brings that world back to me, much like Proust’s madeleine dipped in lemon-scented tea. The book is titled Jump Cuts, but to me it could just as easily be called “Jumping Back,” since it revives my early love for the Surrealists.

Polizzotti explores their world with detours into Bob Dylan and Hitchcock’s Vertigo. Yet the gravitational center remains Surrealism, which makes sense: Polizzotti wrote a superb biography of Breton years ago and has translated numerous Surrealist works. He has also translated Flaubert, Rimbaud, Patrick Modiano, Marguerite Duras, and recently Breton’s classic Nadja for NYRB. Still, Dylan and Hitchcock feel connected here—Dylan’s mid-1960s work and Vertigo both carry a distinctly Surrealist charge.

At the end of the day, though, Surrealism is defined above all by André Breton. Salvador Dalí may be the most famous figure, but Breton was the true wizard behind the curtain. He was also the most eccentric—though not in the flamboyant way Dalí was. Breton’s quiet eccentricities were equally striking. For example, though black-and-white photos never reveal it, his favorite suit color was green. He was deeply interested in sex, yet prudish about certain practices. He disliked homosexuality in theory, but counted gay artists among his friends. His worldview was largely male-oriented, but we now know there was a powerful female Surrealist presence as well—women who were remarkable poets and artists in their own right.

Breton and his circle are significant because they offered a unique and open-ended perspective on the world. Yes, he could be controlling—expelling artists and writers from the movement when they crossed him—but that was more administrative rigidity than creative vision. His doctrine-heavy approach was bound to create friction among artists. It must have been painful at the time, yet reading about these quarrels now often comes across as hilariously absurd.

Jump Cuts is a delightful collection of essays. I especially appreciate what Polizzotti writes about artists wrestling with difficult or controversial subjects, such as a figure like Sade, and about how shutting out such voices is always a mistake. Breton, for all his stubbornness, listened to those he disagreed with. That capacity to listen before responding remains a rare and valuable human skill.

For me, this book feels like something to hold onto in moments of cultural or political despair. In other words, a keeper.

Interesting. Another gem I had not heard of. Does Polizzotti mention Harpo Marx or the Marx brothers, in general? Dali considered Harpo Marx, Disney, and Cecil B. DeMille the only American surrealists in Hollywood at the time.

According to Groucho Marx, Dalí had something of a crush on Harpo, joking: "He was in love with my brother – in a nice way."

I'm currently reading a collection of surrealist tracts called Surrealism Against the Current edited by Michael Richardson and Krystof Fijalkowski. In their excellent introduction they point that contrary to popular belief Breton did not wield absolute authority and note that surrealism was a COLLECTIVE idea, accurately defined by Andre Masson as "the collective experience of individualism." They also quote the non-surrealist Jacques Lacan who described surrealism as "a tornado on the edge of an atmospheric depression where the norms of humanist individualism founder." Expulsions from the movement were justified by the betrayal of the surrealist ideal, and Breton was not the sole arbiter of such expulsions, for example, he opposed the expulsion of Max Ernst in 1953 but was over ruled and went along with the group decision.