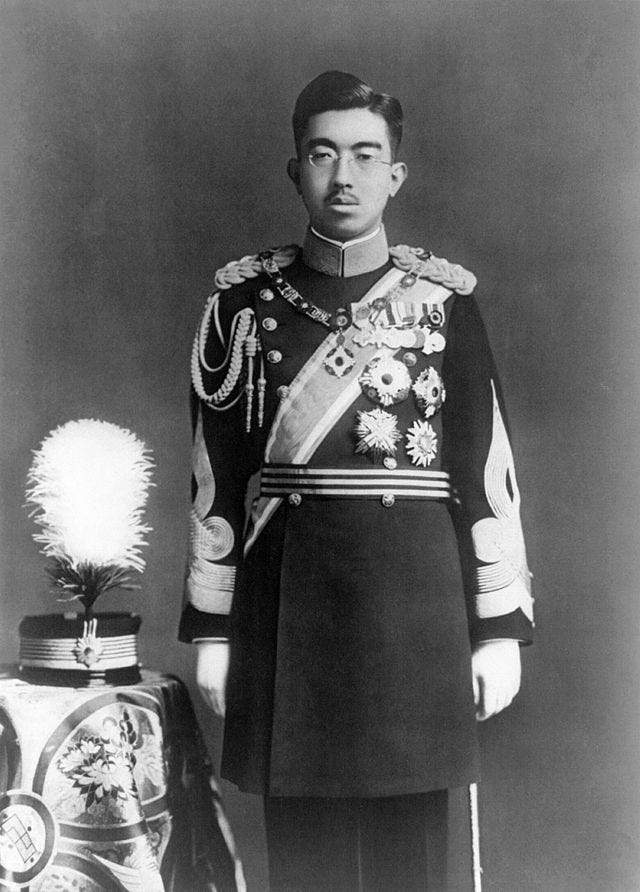

I got the tail-end of the Showa Era when I lived in Japan in 1989/1990. Hirohito was the emperor during the Showa period, in fact, that is how one measures history in Japan. His time period (as well as the Showa era) is from December 25, 1926, to January 7, 1989. There is obviously that incident that happened between our country and Japan, but nevertheless what I find the most fascinating is the film/art/literature culture of that era. Due to the passing of the Emperor, I came upon a series of books and documents regarding the Showa era, when I was there, and each image from the 20th century had a profound effect on me. It is difficult to believe that when I first visited Japan in 1989, I never used chopsticks. The first night there, I had my first proper Japanese meal, and in front of me were these two wooden sticks. I was starving, and when one is in that state, it is incredible how one can master these two wooden sticks to serve the purpose of putting food in your mouth. Also, I loved the thought of eating without stabbing my food on a fork. That to me seems so violent. Yet picking up food gently using chopsticks, somewhat made the meal more tasty to me.

When I was in living in Tokyo and Moji-Ku, I lost track of my culture, due that at the time there was no Internet, and if I wanted to read a newspaper, for instance, the Japan Times (their English language daily paper) I had to wait two to three days before I got the latest edition. So the big news of that time was the Berlin Wall going down and the massive San Francisco earthquake - all news I got two days later after it happened. I felt like a man out of my time, and often like the Man who fell to Earth as well. I would wander around Moji, going from shop-to-shop to coffee shop-to-bar, and all the children would stare at me as I walked by. At the time there were hardly any foreigners walking around, so I must have looked like an alien to them. In fact, perhaps I’m an alien.

My obsession at the time was to collect images of Astro Boy. I was struck by the beauty of the narrative of a robot boy who was invented to replace the inventor’s real son, who died in a car crash. Over his grief, he realizes that the robot son can never replace the “authentic” son he had, so he abandoned Astro Boy. Of course, the robot boy becomes a hero and saves the day - as all superheroes do in their own fashion. Around the same time, “Godzilla” became known, and was of course regarded as a metaphor for nuclear weapons. The creature from the mishap of science would destroy Tokyo, but yet, the city always survives. As a hobby, I like to walk around Tokyo and see the original buildings from that era (the 1960s or 1950s), but it is getting harder to locate, due to the nature of Tokyo always tearing down and putting up new buildings. I have been going there for the last 25 years, and I often feel that Godzilla must have come upon the city again, and “forced” some changes again.

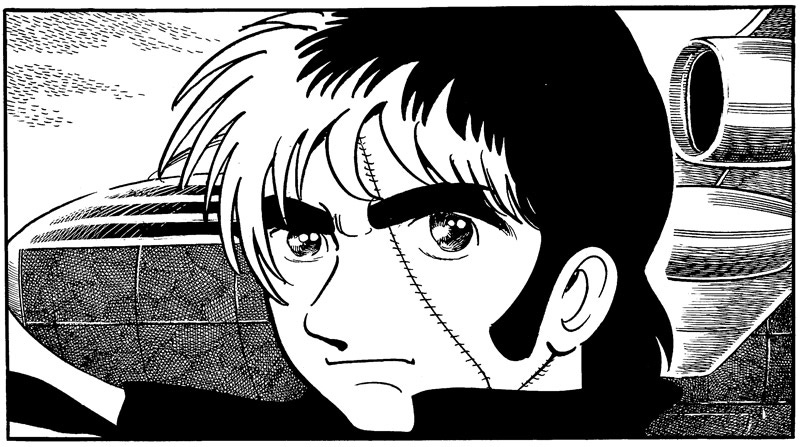

For my own personal choices, I have always preferred the character “Black Jack, ” due that I think he is the most mysterious character in the world of its creator Osamu Tezuka. He’s a doctor, who seemed to fall out of the legal medical world, to travel around Japan to help those in need. The fact that he commits illegal surgeries is of great interest, and quite scary to me as well. The ‘goth’ doctor, if he’s even a real “doctor” strikes me as an original character. For the Japanese reading audience, he may not be so scary, but to me, I think I would be terrified of being on an operating table, and having to face the man/boy with the white streak hair.

On the other hand, I have an emotional pull for Goseki Kokima (the artist) and Kazuo Koike’s (the writer) manga series “Lone Wolf and Cub.” The story is about a wandering assassin who travels with his three-year-old son throughout Japan, in the hopes of seeking revenge on the Yagyū clan. The clashes in the comic are quite violent, but also disturbing with the respect of the son and his father. In a way, it makes me think of the Cormac McCarthy novel “The Road.” Both narratives deal with a father taking care of his son, in a very hostile world. It is almost fairy-tale like in that the bond between father and son is called into question by the daily life of survival at its worst state.

More likely I will never ever know Japan, but I will always be in love with what I think is Japan. The reality and what I imagined is quite a leap into a faith that may be misleading; nevertheless, it’s a world of my own making with the significant assistance of the above.