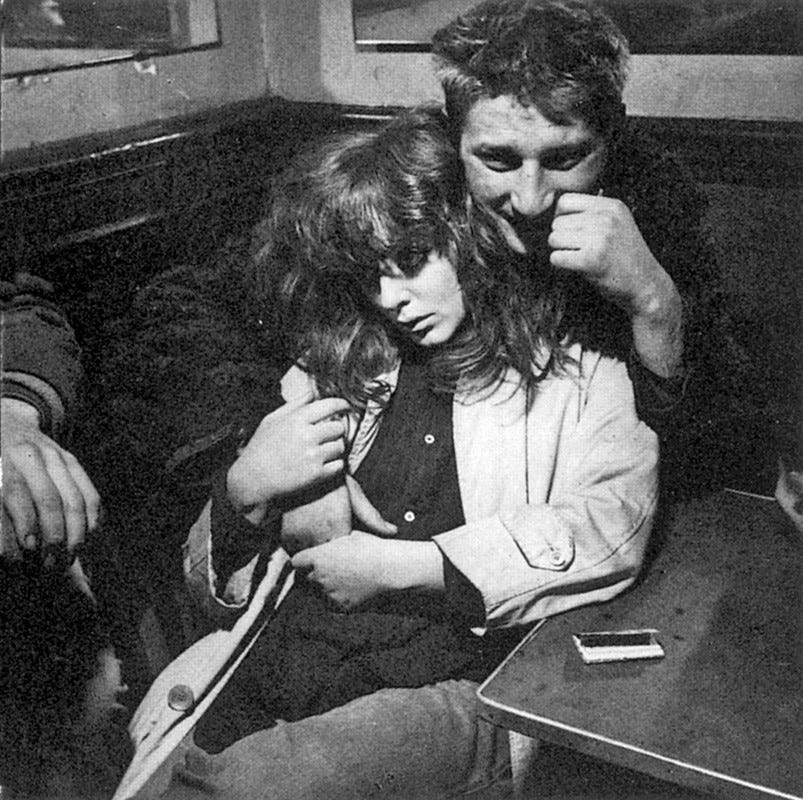

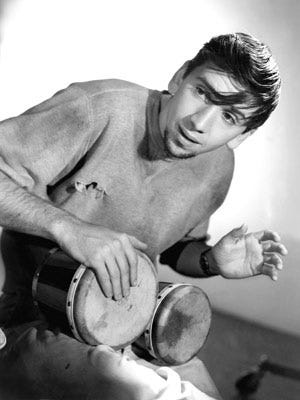

It is strange to see one’s world represented in a book, TV show, or film and realize that you are essentially part of it, but the fact is, you’re not. The first time I have ever seen or heard of a beatnik was Maynard G. Krebs on the “The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis” TV show. The irony is that many consider me the child of the Beats, due to my parents, of course, but mostly how the media portrayed them in various books regarding my father, as well as publications like Look magazine and so forth. Even today, my life is well-documented by others, which I presume know more about me than I know myself. The most extensive archive of images of yours truly is at the Getty Institute, yet I don’t own any of the pictures of myself, nor have I seen them.

One soon realizes that reality or truth is not the primary end-product of journalism or a narrative. I think there is a need to have a description where this is a beginning, a middle, and of course, an end. People have trouble dealing with a narration that is messy or not complete. But the truth is to be human is to be inconsistent with one’s history or time. We often look back to see where we are now, but how can one trust a narrative that is not clearly stated by the subjects themselves but by others who claim to have the story because they read it at so-so’s publication or heard rumors. Concerning my life, what I know is what I don’t know. There are deep mysteries in my life, and I don’t think one can dig them out from the rest of one’s history.

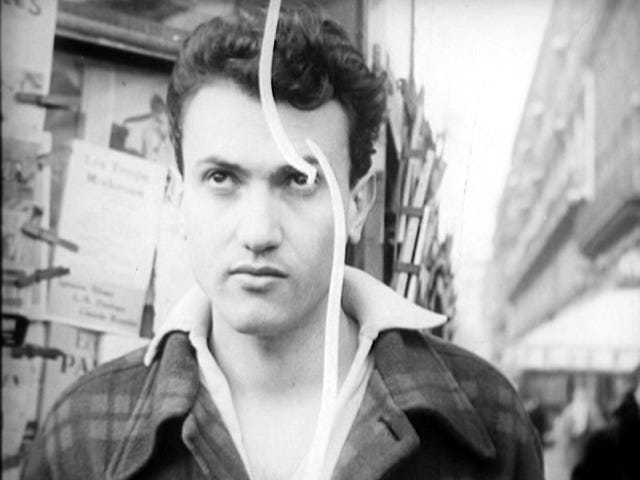

The funny thing is when I do run upon a picture of myself or others at that time, it is how timeless they or everyone looks. When you see Maynard, he seems very dated. Or if you know any film made in the late 50s regarding the alternative social scene or the beats, it looks like someone’s remorseful sense of memory. Mainstream cinema has never portrayed an alternative world correctly. I think due that the filmmakers have very little knowledge of that world. Or perhaps it has something to do with the camera, that truth looks into the viewfinder, and fiction comes out at the other end.

It must have been bizarre for Jack Kerouac to walk into a room, and everyone knows who he is and what he is. The truth is one doesn’t know who he is; they presume that they know, when in fact, their knowledge is, at its best, second-hand gossip. Although not famous in the sense of Kerouac (of course), I feel the “eyes” look at me as I enter a room full of strangers. They know who I am, but I haven’t the foggiest idea who they are. They already have an opinion of me, yet I am clueless about who these people are.

I have consistently preferred the world of shadows to bright sunshine. My natural playground is the freedom to walk among the shadow images of tall buildings and various trees that stand monumental in certain parts of downtown Los Angeles. Seeing myself in a book of someone else’s making strikes me as a false image because it is a photograph that was made in a second, and so far, my life has almost reached 68 years. Yet one is judged by an image that took seconds, and I must somehow live that ‘dream’ for others. The truth is I refuse to. The spectacle wants its narrative, and I refuse to partake in someone else’s sense of what is a description. The only narrative I am interested in is that I write or produce. Be aware of false footnotes in history; our memory is only as good as what we want to believe.

“We tell ourselves stories in order to live...We look for the sermon in the suicide, for the social or moral lesson in the murder of five. We interpret what we see, select the most workable of the multiple choices. We live entirely, especially if we are writers, by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images, by the "ideas" with which we have learned to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience.” ― Joan Didion, The White Album