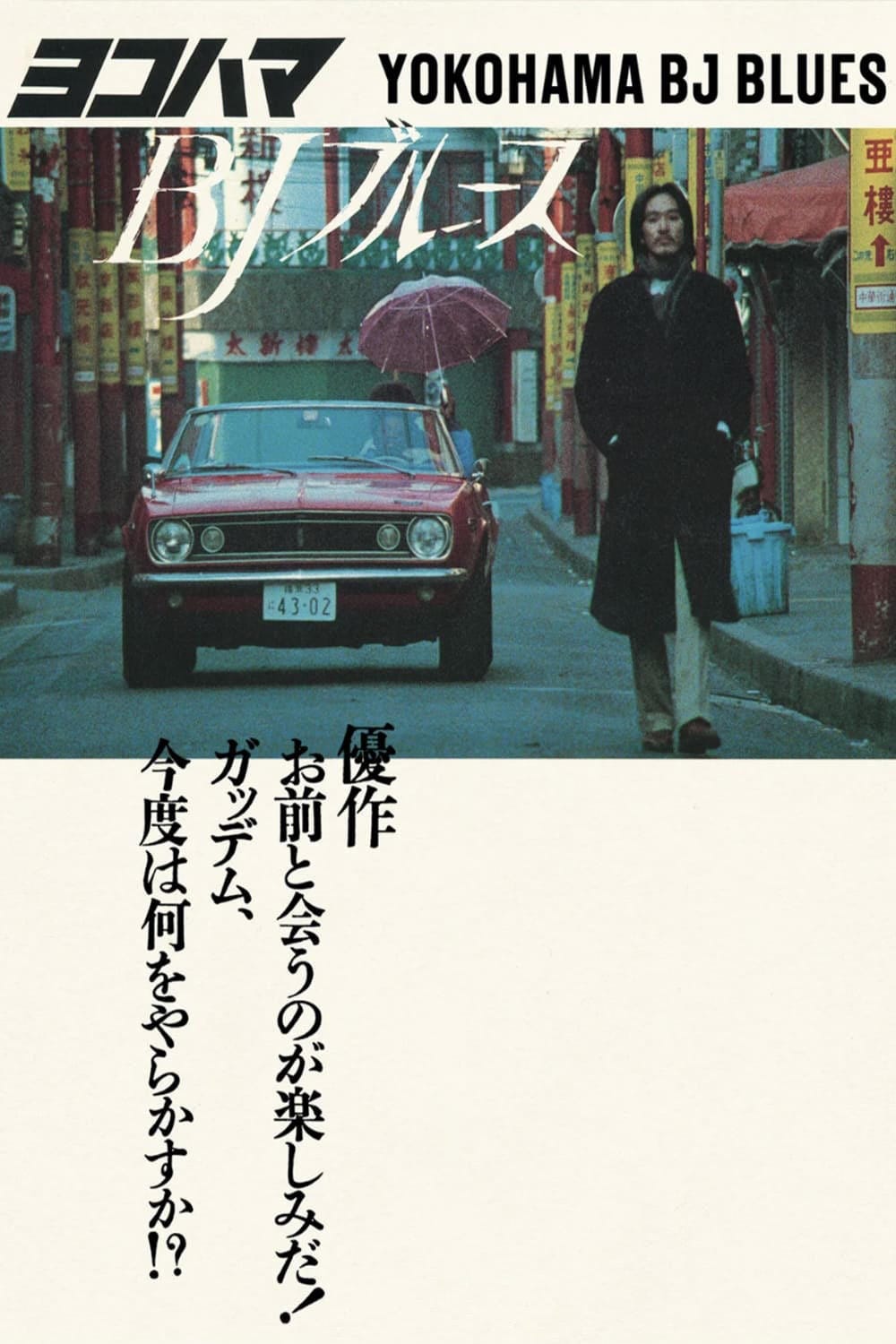

Yokohama BJ Blues (1981)

Drifting Through Yokohama: Watching Yūsaku Matsuda’s Noir

My wife, Lun*na Menoh, and I have been enjoying a new streaming channel for us called OVIDtv, which is very carefully curated. It’s like MUBI, but smaller, and focused entirely on independent films—many with a Leftist viewpoint, which suits me perfectly. 98% of their catalog is unfamiliar to me, so it feels like discovering a whole new world I somehow missed.

It reminds me of when I was a young teenager and there was a strange TV station that broadcast only the most obscure shows. We used rabbit ears on our set, and I had to position them just right, as if the signal were coming from outer space. All the commercials were from local used car lots along Olympic Boulevard near Downtown Los Angeles. The only show I remember from that station is Circus Boy, starring a very young Mickey Dolenz of The Monkees.

OVIDtv feels like that forgotten station—though with completely different aesthetics. One film that impressed us was Peter Watkins’ La Commune (all six hours of it). Another that stayed with me was Eiichi Kudo’s Yokohama BJ Blues (1981). The story is by its star, Yūsaku Matsuda, who also brought Kudo to the project. Technically he is not listed as the Producer, but it was his stardom that got the film made, and it isn’t a masterpiece, but it contains some fantastic elements.

It’s a noir story about a gigging musician who plays in a bar and moonlights as a private detective. He takes a case to find the missing adult son of a mother desperate to bring him home. Watching it, I thought of Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye, based on Raymond Chandler’s novel. Just as Altman captured the essence of 1970s Los Angeles, Kudo’s film is rooted in Yokohama, with the city itself as much a character as any of the people on screen.

The cinematography by Seizō Sengen makes full use of long shots, echoing the feel of New American Cinema of the 70s. The muted yet vibrant colors give the sense of drifting through an endless night, only to collide with the harshness of dawn. Each character is sketched with flair, and the underworld of Yokohama carries a subtle homoerotic charge.

By contrast, much of contemporary Japanese cinema now resembles television—visually flat and unremarkable, as though everything in the frame is treated as equal. This is striking when you consider how the great Japanese films of earlier decades reveled in visual beauty, often transforming landscapes into something near-mythic. That tradition carries through in Yokohama BJ Blues, which, while uneven, still reminds us of the power of cinema to shape how we see the world.